Should Teachers Be Allowed to Voice Their Political Opinions?

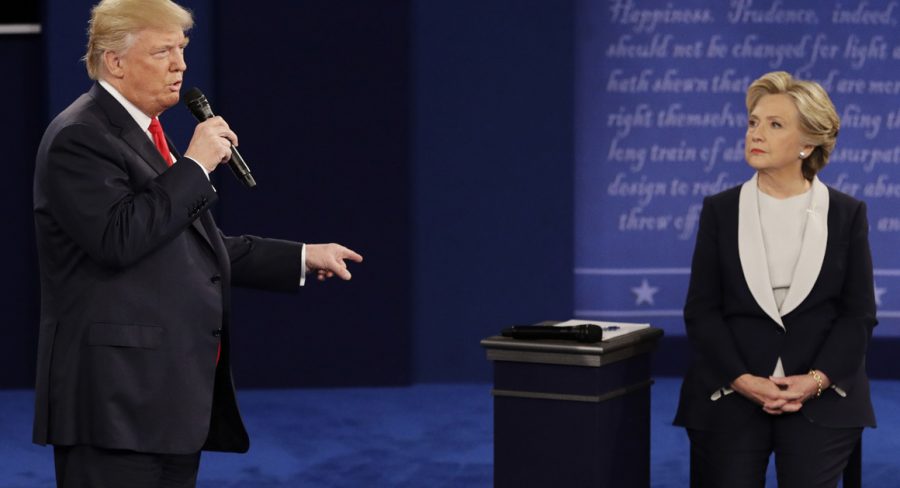

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump answers Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton during the second presidential debate at Washington University in St. Louis, Sunday, Oct. 9, 2016. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Almost every student at John Jay High School knows not to ask their teachers about anything pertaining to politics, but why has this precedent developed? The obvious reasoning is that it would be wrong for teachers to force their political beliefs onto students who are uneducated about the topic. All history and government classes at John Jay delve into important political information of our world’s past and present. However, there is something that holds back our learning: we don’t know what we are supposed to think. Personally, I am rather lost when it comes to modern day politics. I can identify a few key figures and understand some modern day issues. Despite this, there is much more that confuses me.

People tend to believe that teachers have a massive influence on the formation of our beliefs, and that we “children” will automatically agree with anything they say, but this is false. In high school, we are all mature enough to make our own decisions and not change our opinions after hearing a teacher’s position. I believe teachers should be allowed to voice their opinions because have an open discussion on their background and how this forms their opinion. This questioning helps students understand the issue and one side of the argument.

Lastly, during our Socratic seminars, students are allowed to voice their opinions, but teachers are not. This lets students who are less educated than their teachers force their opinions on other students to try to convince them they are right. It is arguable that teenagers have a higher influence on other teenagers than teachers do. This is what occurs in our schools, but teachers who have a much more educated opinion and no intent to force their beliefs on students are forced to keep their mouth shut. Thus, we must let teachers share their political beliefs to help educate the student body

Chandler Lewis • Feb 8, 2017 at 12:26 pm

While I understand your position — that teachers’ well thought-out political stances can be instructional — teachers are not people. We are entities employed by the state and directed by the local communiity to “deliver instruction”; that is, we don’t exist as people with independent views, but rather as tools for the dissemination of curricular knowledge or practitioners of skills that we encourage proto-practitioners to develop. But my own “personal” identity does not exist in the classroom. My religion, my view on social matters, my musical taste, my politics all cease to exist when I knot the tie and enter district property. In Socratic seminar I am a facilitator, urging students not to “adopt ideas” but to create a space — all that empty space in the middle of the room — where every student can hold aloft an idea, examine its worth, and ultimately decide if it’s something s/he wants to accept or fight against. All I do is make sure no one interrupts that process. The moment I speak in seminar, the nature of it as a free market of ideas is destroyed by the notion that I am more of an authority, that my idea is the right idea, that somehow my gradebook is open, red pen hovering.

Stay with me, because I’m getting to the part that begged the question you have brought into focus. The recent election has both caused more students to seek answers and more teachers to re-evaluate the curricula we teach. As an English teacher, I tell my students composing college essays that they cannot lie, distort or embellish the autobiographical facts of their high school careers, their accomplishments and their history, because such alternative facts are lies. When a student points out that lying, deceiving and distorting are exactly the way one can achieve great heights — as high as the highest office in the land — then my curriculum and the fundamental notions upon which it is built are called into question.

I began this year — long before the election — asking my students to examine widely-held, bi-partisan, and authoritative definitions of White Supremacy, racism, bigotry and chauvinism, spending some time describing how those in power who use that power to demean or dehumanize or disempower another group of people because of race, sexual orientation, creed or religion are indeed racists, homophobes, Anti-Semites. Recently, students have come to me confused by the actions of people in power who do these things (demean, dehumanize, and attempt to disempower entire religions or cultures). They wonder, wait, isn’t this wrong? What this person is doing? Now, the curriculum we studied indeed defines this powerful person as a racist and White Supremacist. Am I allowed to say President Trump fits that definition exactly? There is a sign on my classroom wall enumerating Laurence Britt’s 14 characteristics of fascism, posted by the history class that shares my room and who have been studying fascist governments. When a student mistakes it for an anti-Trump poster, am I allowed to ask questions about why they might suppose it is?